From the Golden Age of Discovery to the Inquisition, Portuguese Jewry went from the heights of wealth and success to the depths of anguish and despair.

The history of Portugese Jewry is like that of many other places, where success and sadness go hand in hand. Walking along Lisbon’s streets, remnants remain of Portugal’s rich Jewish life. Sparks of Portugal’s past can be found in the remote mountain villages, where the some of the last remaining Marrano communities can still be found practicing Jewish rituals behind closed doors, fear of persecutions still looming. Today, the Jewish community of Portugal numbers approximately 600 people.

The history of Portuguese Jewry is like that of many other places, where success and sadness go hand in hand. Walking along Lisbon’s streets, remnants remain of Portugal’s rich Jewish life. Sparks of Portugal’s past can be found in the remote mountain villages, where the some of the last remaining Marrano communities can still be found practicing Jewish rituals behind closed doors, fear of persecutions still looming. Today, the Jewish community of Portugal numbers approximately 600 people.

Several important Jewish communities were already active when the kingdom of Portugal was founded in the 12th century. During the first dynasty, Jews enjoy relative protection from the crown. The crown recognized the Jewish community as a distinct legal entity and appointed specific rulers to adjucate their cases. King Afonso Henriques (1139-85) entrusted Yahia ben Yahi III, a Jew, with the role of royal tax collector and supervisor; Yahia be Yahi III also became the first chief Rabbi of the Portuguese Jewish community. Yahia ben Yahi’s grandson, Jose ben Yahi was appointed High Steward of the Realm, by Henriques’ successor, King Sancho I (1185-1211).

Tensions arose between the Jewish community, who choose to remain faithful to their religion, and the local clergy and middle/lower classes. The clergy wanted to invoke restrictions of the Lateran Council against the Jews, but King Dinis (1279-1235) resisted and reassured the Jews that they did not have to pay tithes to the church.

Golden Age of Discovery

Jews lived in separate quarters, but had freedom to move within the country; these quarters remained until the Jewish expulsion from Portugal.

The 13th and 14th centuries were known as Portugal’s Golden Age of Discovery, in which Jews made a major contribution to Portugal’s success. In the early 14th century, more than 200,000 Jews lived in Portugal, which was about 20 percent of the total population.

Jews lived in separate quarters, but had freedom to move within the country; these quarters remained until the Jewish expulsion from Portugal. Each of these quarters had its own synagogue, slaughter house, hospital, jails, bath houses and other institutions. A rabbi served as the administrative and legal authority within the commune.

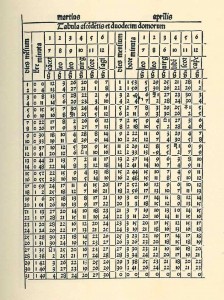

Portugal was home to many famous Jews during this period. Abraham Zacuto wrote tables that provided the principal base for Portugese navigation, including those used by Vasco Da Gama on his trip to India. Guedelha-Master Guedelha served as a rabbi and doctor and astrologer for both King Duarte and King Alfonso V. Isaac Abravanel was one of the principal merchants and a member of one the most influential Jewish families in Portugal. Another figure, Jose Vizinho, served as doctor and astrologer to King Joao II. Joao II also sent the Jew, Abraham de Beja, on many voyages to the East.

Jews became the intellectual and economic elite of the country. Jews were involved in all aspects of the explorations, from financing the sailing fleets to making scientific discoveries in the fields of mathematics, medicine and cartography. Many were employed as physicians and astronomers as well royal treasurers, tax collectors and advisors. It was common to see Jews adorned in silk clothing, carrying gilt swords and riding beautiful horses. They were given preferential treatment by the kings.

Jews became the intellectual and economic elite of the country … Many were employed as physicians and astronomers as well royal treasurers, tax collectors and advisors.

Jealous of the Jews’ success, anti-Jewish sentiment arose in the peasant and middle classes. Fights between Jews and Christians became more common after the influx of Jews from Spain into Portugal, in 1391.

During the reign of King Joao I (1385-1433), Jews were forced to wear a special habit and to obey a curfew. Joao’s successor, King Duarte (1433-1438), introduced laws forbidding Jews from employing Christians. A reprieve took place during King’s Alfonso V’s rule, when many of these restrictions were repealed.

In 1492, King Ferdinand and Isabella of Spain expelled all the Jews from Spain. More than 150,000 Spanish Jews came to Portugal seeking permanent refuge. King Joao II of Portugal allowed them to enter because he was preparing for war against the Moors and wanted to take advantage of their wealth and expertise in weapon-making. At a price of 100 Cruzados a family, 630 wealthy Jewish families were granted permanent residence. A number of craftsmen, skilled in making weapons, were also allowed to become permanent residence. The rest were permitted to stay in Portugal for eight months, upon payment of 8 cruzados per adult. At the end of those eight months, shipping was still not available, so the King forfeited Jewish liberty and declared the remaining Jews slaves.

Another tragedy befell the Jewish community in 1493, when the King ordered the separation of Jewish children from their parents. Seven hundred children were sent to the newly discovered island of Sao Tome, off west coast of Africa. In 1993, descendants of those children held a ceremony commemorating the event.

Expulsion from Portugal

Following King Joao’s death in 1494, Manuel I ascended to the throne and restored the Jews’ freedom. His legitimacy as heir to the throne was challenged, so he decided to solidify his position by marrying Princess Isabel of Spain. Isabel told Manuel that she would only marry him if he expelled the Jews. Their marriage contract was signed on November 30, 1496, and, five days later, he issued a decree forcing all Jews to leave Portugal by October 1497.

Manuel was never content with his decision, mainly because he appreciated the economic value of the Jews to the country. To make it more difficult for Jews to leave, he made Lisbon the only viable port of exit. He also tried to convert as many Jews to Christianity as he could to keep them in Portugal.

On March 19, 1497 (the first day of Passover), Jewish parents were ordered to take their children, between the ages of four and fourteen, to Lisbon. Upon arrival, the parents were informed that their children were going to be taken away from them and were to be given to Catholic families to be raised as good Catholics. Children were literally torn from their parents and others were smothered, some parents chose to kill themselves and their kids rather than be separated. After awhile, some parents agreed to be baptized, along with their children, while others succumbed and handed over their babies.

In October 1497, about 20,000 Jews came to Lisbon to prepare for departure to other lands. They were herded into the courtyard of Os estaos, a palace and were approached by priests trying to convert them. Some capitulated, while the rest waited around until the time of departure had passed. Those who did not convert were told they forfeited their freedom and would become slaves. More succumbed. Finally the rest were sprinkled with baptismal waters and were declared “New Christians.”

Inquisition Period

While many of the New Christians accepted their religion, many chose to continue practicing Judaism behind closed doors, while publicly practicing Catholic rituals; they became known as Marranos or crypto-Jews. The Portugese majority still considered the “New Christians” Jews, despite their outward affiliation with Christianity. Claims against the Marranos were presented to the King, along with a list of crypto-Jews.

In 1506, 3,000 “New Christians” were massacred in Lisbon. Afterward, King Manuel executed 45 of the main culprits who had incited the mob.

Popular support for a Portuguese Inquisition surfaced in 1531, when many Christians blamed the New Christians for the recent earthquake. Pope Clement VII authorized the Inquisition and the first auto-da-fe (trial) took place in Lisbon on September 20, 1540.

The right to seize and confiscate the property of the accused led to the arrest of every prominent “New Christian” family. Once arrested, death was only escaped if one admitted to Judaizing and implicated friends and family. Other sentences included public admission of the alleged sins, the obligatory wearing of a special penitential habit and burning at the stake. Urged by greed, eventually even genuine Christians were martyred.

Among those murdered were many famous Jews of the period, including Isaac de Castro Tartas, Antonio Serrao de Castro and Antonio Jose da Silva, who was later known as “The Jew.”

Attempting to evade the Inquisition, many Portuguese Marrano families fled to Amsterdam, Salonika and other places across the Old and New worlds. In 1654, 23 Portugese Jews arrived in New Amsterdam (New York) and became the first Jewish settlers in the United States. The stream of refugees did not stop until the end of the Inquisition in the late 18th century. The last public auto-de-fe took place in 1765; however, the Inquisition was not formally disbanded until after the liberal revolt in 1821.

Resettlement

Around 1800, Portugal decided to “invite Jews” back into the country and reverse Portugal’s economic decline. The first Jewish settlers to come were British. Tombstones, written in Hebrew and dating back to 1804, can be found in a corner of the British cemetery in Lisbon. Other Jewish immigrants came from Morocco, Tangiers and Gibraltar. Official recognition to the Jewish community was not granted until 1892. After granting the community recognition, Shaare Tikvah synagogue was built in Lisbon, however, the synagogue was not allowed to face the street.

Conversions to Catholicism were still frequent though in the 1920’s, splitting families; this tendency declined by the 1950’s.

To read more click here.