Prof. Yehoshua Ben Arieh: ‘Palestinian Breakout To Sinai Illustrates Need To Find Territorial Solution For Gaza Strip’

‘Impossible To Resolve Israeli-Palestinian Conflict Without Solution To Gaza’

‘Solution Is A Trilateral Land Swap Between Israel, Palestinians And Egypt’

In a dramatic new development, over one-hundred thousand Palestinians burst through Egyptian security forces into Sinai. An estimated one and half million Palestinians are closed-off in the Gaza Strip by Israel in the north and Egypt to the south. Ruled by the fanatical Hamas Islamists, they refuse to accept Israel’s right to exist and continually rocket the nearby Israeli town of Sderot. In response, Israel has closed off its border and reduced its supplies of power and fuel. The situation in Gaza has turned from bad to worse while Israeli and Palestinian negotiators from the West Bank try to make progress in their peace contacts. In an interview with IsraCast, Israeli geographer Prof. Yehoshua Ben-Arieh presents a land exchange plan between Israel, the Palestinians and Egypt that he believes could lead to a breakthrough.

Listen to Audio Interview with Prof. Ben-Arieh

The Israeli-Palestinian confrontation took a new twist after tens of thousands of Palestinians from the Gaza Strip broke through Egyptian security forces and headed into Sinai to buy ought shops in the nearby town of Raf. The Palestinian ‘invasion’ came in response to the Israeli closure of Gaza terminals to Israel and the reduced Israeli supplies of power and fuel-part of an Israeli reaction to the more than 4,000 Qassam rockets and mortars that have turned the Israeli town of Sderot into a ghost town. Israeli geographer Prof. Yehoshua Ben – Arieh warns that the Palestinian break- out into Sinai again proves the need to find a territorial solution to the problem of the one and a half million Palestinians living inside the ‘cage’ of Gaza. In his view, the Gaza Strip is now the main obstacle to resolving the conflict.

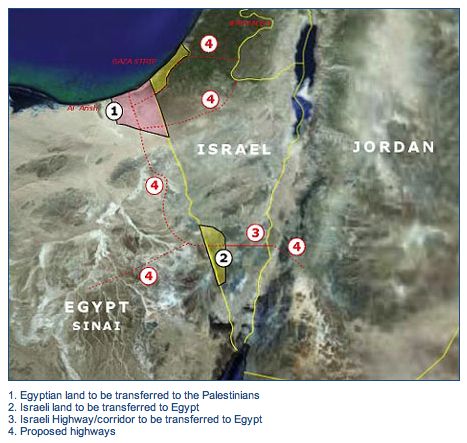

Ben-Arieh proposes that Israel give a small piece of land from its southern Negev in the area of Wadi Paran on the border of Egyptian Sinai which would become Egyptian territory. Egypt could then build a land bridge to Jordan that could also transfer Egyptian – owned oil, gas and water pipelines. In return for this land, Egypt would transfer an area similar in size ( around 600 square kilometers) located to the south of Rafah in the Gaza Strip. The coastline would extend 20 kilometers towards El-Arish from the present Israeli – Egyptian border and the area would extend inland into Sinai from the coast. In lieu of the territory that the Palestinian Authority would receive from Egypt, the PA would agree to transfer to Israel a similar area in size to Israel – exactly the same area that it will get from Egypt south of Rafah. This would involve West Bank land around the Israeli towns of Maale-Adumim, Jerusalem and Ariel.

Ben-Arieh proposes that Israel give a small piece of land from its southern Negev in the area of Wadi Paran on the border of Egyptian Sinai which would become Egyptian territory. Egypt could then build a land bridge to Jordan that could also transfer Egyptian – owned oil, gas and water pipelines. In return for this land, Egypt would transfer an area similar in size ( around 600 square kilometers) located to the south of Rafah in the Gaza Strip. The coastline would extend 20 kilometers towards El-Arish from the present Israeli – Egyptian border and the area would extend inland into Sinai from the coast. In lieu of the territory that the Palestinian Authority would receive from Egypt, the PA would agree to transfer to Israel a similar area in size to Israel – exactly the same area that it will get from Egypt south of Rafah. This would involve West Bank land around the Israeli towns of Maale-Adumim, Jerusalem and Ariel.

He envisages the possibility of building a Palestinian sea and air port in the new area and economic development to raise the poor standard of living of Gaza residents. The Egyptians would also gain an important economic asset by being able to build the land bridge leading to Jordan, Saudi Arabia and the rest of the Arab world. All three sides, the Palestinians, Egypt and Israel would benefit from such a territorial swap – neither side would lose any territory in what is a realignment serving the interests of all three parties. Ben-Arieh notes that the idea of territorial exchange is not new in the Arab world – Jordan and Saudi Arabia redrew their borders in order to allow Jordan to expand its Red Sea port at Aqaba.

He envisages the possibility of building a Palestinian sea and air port in the new area and economic development to raise the poor standard of living of Gaza residents. The Egyptians would also gain an important economic asset by being able to build the land bridge leading to Jordan, Saudi Arabia and the rest of the Arab world. All three sides, the Palestinians, Egypt and Israel would benefit from such a territorial swap – neither side would lose any territory in what is a realignment serving the interests of all three parties. Ben-Arieh notes that the idea of territorial exchange is not new in the Arab world – Jordan and Saudi Arabia redrew their borders in order to allow Jordan to expand its Red Sea port at Aqaba.

Ben-Arieh has met with representatives of Israel, the Palestinians and Egypt as well as American officials. While all have expressed an interest in his initiative they said the question is not just territory but the very issue of recognizing Israel as a Jewish state. However, Ben-Arieh argues that the very essence of his plan is ideological because it is based on the concept of a two state solution that is possible to implement. At the recent Annapolis conference in the U.S., Arab League states showed their readiness to play a role in resolving the Israeli- Palestinian conflict. Ben-Arieh says that after the recent developments in Gaza, the time has come to put them to the test by reconvening Annapolis to discuss his territorial exchange which he is convinced can help resolve the conflict.

Gaza into Egypt

Middle East Strategy at Harvard

Martin Kramer

‘This may be a blessing in disguise.’ This is how an unnamed Israeli official greeted the destruction by Hamas of a chunk of the border barrier separating Gaza from Egypt, followed by an unregulated flood of hundreds of thousands of Gazan Palestinians across the border into Egypt. ‘Some people in the Defense Ministry, Foreign Ministry and prime minister’s office are very happy with this. They are saying, ‘At last, the disengagement is beginning to work’. Obviously, a broken border between Egypt and Gaza is a major security problem for Israel. But war matériel and money for Hamas crossed the border anyway. An open border effectively absolves Israel of responsibility for the well-being of Gaza’s population, and may prompt Israel to sever its remaining infrastructure and supply links to Gaza. A large part of the responsibility for Gaza would be shifted from Israel to Egypt, which might explain the satisfied murmurings in Jerusalem.

But the implications of the big breach go further. Given that Gaza and the West Bank are unlikely to be reunited, the question of Gaza’s own viability as a separate entity is bound to resurface. In the 1990’s, economists talked about Gaza’s viability as a function of economics: massive investment could turn it into a high-rise Singapore. But in an article written back in the summer of 1991, a leading geographer argued that this wasn’t feasible, and that a viable Gaza would need more land. Most of it, he argued, would have to come from Egypt.

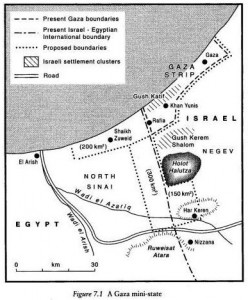

‘Gaza Viability: The Need for Enlargement of its Land Base’ – that was the title of an article by Saul B. Cohen, a distinguished American geographer and one-time president of Queens College and the Association of American Geographers. Cohen began with this basic assumption: a high-rise Gaza ‘would be ecologically disastrous… To become a successful mini-state, one that would serve as a ‘gateway’ or exchange-type state, Gaza will need additional land.’ Cohen calculated that a viable Gaza would need about 1,000 square kilometers of territory – that is, an additional 650 square kilometers. This is how he mapped his proposal:

Egypt would provide a 30-kilometer stretch of Mediterranean coast (200 square kilometers), giving an expanded Gaza a total Mediterranean coast of about 75 kilometers .Egypt would also provide a stretch of the north Sinai plain (300 square kilometers), and Israel would kick in a parcel on its side of the border (150 square kilometers). This would be sufficient area, Cohen wrote, ‘to relieve Gaza’s overcrowding, provide for agricultural and natural land reserves, and spread urban activities (including small towns and hotels) to provide a unique, low-rise cultural landscape.’ Egypt would provide water (by extending a Nile water canal from El Arish) and power (via a natural gas line). Cohen also believed that Israeli settlements at Gush Katif ‘in the long run should be removed.’ The long run didn’t take all that long.

The Oslo accords eclipsed the idea of a Gaza mini-state.Gaza was supposed to find its outlet in the West Bank, through a safe-passage corridor. The idea of an expanded Gaza was revived shortly before Israel’s unilateral withdrawal, by an Israeli geographer (and former rector of Hebrew University), Yehoshua Ben-Arieh. He proceeded from this assumption: a corridor to the West Bank would not suffice to relieve the pressure building up in Gaza. Gaza could only be viable if it became a crossroads or gateway, which would require a deep-water port, an airport, and a new city. Ben-Arieh proposed a three-way swap. The Palestinian Authority would be given 500 to 1,000 square kilometers of Egypt’s northern Sinai. Israel would give Egypt 250 to 500 square kilometers along their shared border at Paran, and would also give Egypt a corridor road to Jordan. On the West Bank, the Palestinian Authority would cede to Israel the same amount of territory (500 to 1,000 square kilometers) it received in Egypt. This is how Ben-Arieh mapped the southern part of his plan:

The Oslo accords eclipsed the idea of a Gaza mini-state.Gaza was supposed to find its outlet in the West Bank, through a safe-passage corridor. The idea of an expanded Gaza was revived shortly before Israel’s unilateral withdrawal, by an Israeli geographer (and former rector of Hebrew University), Yehoshua Ben-Arieh. He proceeded from this assumption: a corridor to the West Bank would not suffice to relieve the pressure building up in Gaza. Gaza could only be viable if it became a crossroads or gateway, which would require a deep-water port, an airport, and a new city. Ben-Arieh proposed a three-way swap. The Palestinian Authority would be given 500 to 1,000 square kilometers of Egypt’s northern Sinai. Israel would give Egypt 250 to 500 square kilometers along their shared border at Paran, and would also give Egypt a corridor road to Jordan. On the West Bank, the Palestinian Authority would cede to Israel the same amount of territory (500 to 1,000 square kilometers) it received in Egypt. This is how Ben-Arieh mapped the southern part of his plan:

Ben-Arieh presented his idea and maps to then-prime minister Ariel Sharon, who (according to Ben-Arieh) described the plan as premature, but didn’t reject it. ‘Maybe one day it can become an idea,’ he reportedly said.

To anyone who knows the complexities of the politics, these plans look fantastic. But while geographers often miss the devilish details, they do have an appreciation of how tentative the map of the Middle East really is. It is a schematic representation of other forces, and if the strength of those forces changes, the map will ultimately show it. There were 350,000 Palestinians in Gaza in 1967. Now there are 1.3 million, who are pushing against the envelope of Gaza’s narrow borders with growing force. Israel has the power and the resolve to push back. Egypt just doesn’t, which is why the envelope burst where it did.

To anyone who knows the complexities of the politics, these plans look fantastic. But while geographers often miss the devilish details, they do have an appreciation of how tentative the map of the Middle East really is. It is a schematic representation of other forces, and if the strength of those forces changes, the map will ultimately show it. There were 350,000 Palestinians in Gaza in 1967. Now there are 1.3 million, who are pushing against the envelope of Gaza’s narrow borders with growing force. Israel has the power and the resolve to push back. Egypt just doesn’t, which is why the envelope burst where it did.

That pressure will not relent, and since Hamas seeks to channel it into a ‘right of return’ on the ruins of Israel, which the United States says it rejects, the question is this: where does Washington propose to divert this pressure? Can its ‘peace process’, now focused entirely on the West Bank , divert any of it? Unless the White House can make water flow uphill, perhaps now is time to revisit the geographers’ alternatives, and honestly ask whether they’re more fantastic than the present policy.